Where Good Ideas Come From

The Natural History of Innovation

What's it about?

Where Good Ideas Come From by Steven Johnson delves into the origins of creativity and innovation. Johnson explores the environments and conditions that foster brilliant ideas, debunking the myth of the solitary genius in favor of networks and open platforms where ideas can mingle and evolve. Through historical anecdotes and scientific research, the book identifies seven key patterns, such as the "adjacent possible" and "liquid networks," that are crucial in sparking breakthroughs. It's a compelling read for anyone looking to enhance their creative potential or understand the dynamics of innovation.

About the Author

Steven Johnson is an American author and popular science communicator known for exploring the intersection of science, technology, and personal experience. His works, including "Everything Bad is Good for You" and "How We Got to Now," present complex ideas with clarity and a narrative drive, often focusing on innovation and intellectual history.

10 Key Ideas of Where Good Ideas Come From

Embrace the Adjacent Possible to Unlock New Innovations

The concept of the 'Adjacent Possible' suggests that innovative ideas are often a step away from our current knowledge or capabilities.

By exploring the boundaries of what is already known or possible, individuals and organizations can unlock new innovations.

This approach encourages looking at existing technologies, ideas, or systems in novel ways to find the next adjacent possibility.

It's about understanding that innovation doesn't always come from a leap into the unknown but rather from expanding the perimeter of the currently possible.

Learn DeeperKeep a Curiosity Journal: Every day, jot down questions or ideas that intrigue you, no matter how unrelated they might seem to your current projects or knowledge. This habit can help you identify patterns or connections you might otherwise overlook.

Cross-Pollinate Your Interests: Actively seek out information, hobbies, or conversations outside your usual sphere. For example, if you're a software developer, try attending a local art exhibit or reading about environmental science. The goal is to expose yourself to the 'adjacent possibles' in other fields that could inspire innovative ideas in your own.

Host Idea Dinners: Organize casual dinners with friends or colleagues from different backgrounds. Make it a point to discuss what everyone is working on or curious about. These conversations can spark ideas that are just on the edge of your current projects or knowledge base.

Implement '15-Minute Experiment Time': Dedicate 15 minutes a day to experimenting with something new related to your work or interests. It could be as simple as using a new software tool, sketching a product idea, or writing in a style you're not accustomed to. This practice encourages exploration right next to your current capabilities.

- Example

A mobile app developer reads about ancient navigation techniques for fun and becomes inspired to create a location-based game that uses historical exploration methods. This idea was an 'adjacent possible' because it combined existing GPS technology with a novel application inspired by an unrelated field.

- Example

A high school teacher interested in history starts using virtual reality in her classroom to create immersive experiences for her students. The idea came from her hobby of gaming. Recognizing the potential of VR to make historical events more relatable, she expanded her teaching methods into new, innovative territories.

Foster Liquid Networks for Enhanced Idea Flow

Liquid networks provide an environment where ideas can flow freely and recombine in new, innovative ways.

These networks are characterized by their fluidity and the ease with which information moves within them.

Creating spaces—both physical and virtual—that encourage serendipitous connections between diverse groups of people can lead to the emergence of breakthrough ideas.

The key is to facilitate environments where barriers to information exchange are minimized, allowing for a rich cross-pollination of thoughts and disciplines.

Learn DeeperJoin diverse online communities and forums related to your interests and beyond. Engage in discussions, share your ideas, and be open to feedback. This digital networking can mimic the fluidity of liquid networks by connecting you with a wide array of perspectives.

Create or participate in interdisciplinary workspaces or groups, whether they're co-working spaces, online collaboration platforms, or cross-departmental projects at work. The goal is to immerse yourself in environments where you can interact with people from different fields and backgrounds.

Organize or attend regular meetups and workshops that focus on creativity, innovation, or specific interests. These gatherings are excellent for sparking new ideas through conversations and presentations, embodying the principle of liquid networks.

Keep a digital tool or notebook handy to jot down ideas, thoughts, and inspirations as they come. This practice helps in capturing the fleeting connections made in these liquid networks and can serve as a basis for future innovations.

- Example

A software developer joins an online forum dedicated to sustainable technology. Through discussions, they collaborate with environmental scientists and entrepreneurs to develop a new app that helps users track and reduce their carbon footprint.

- Example

A graphic designer working in a co-working space regularly interacts with professionals from various industries. One day, a casual conversation with a biologist about patterns in nature inspires a new design approach that becomes highly sought after in the design community.

Harness the Power of Slow Hunches for Breakthrough Discoveries

Slow hunches are ideas that develop over time, gradually maturing into fully formed concepts or solutions.

Recognizing the value of these slow-burning insights requires patience and the willingness to nurture and develop them over extended periods.

Encouraging an environment where slow hunches are valued means allowing for long-term projects and investigations, even if they do not yield immediate results.

This approach acknowledges that some of the most groundbreaking ideas need time to evolve and cannot be rushed.

Learn DeeperKeep a Journal: Start documenting your thoughts, ideas, and observations on a daily basis. This practice can help you track the evolution of your slow hunches over time, making it easier to connect dots that were not initially apparent.

Dedicate Time for Reflection: Set aside regular intervals for quiet reflection or meditation. Use this time to think deeply about your ongoing projects or ideas, allowing your subconscious mind to work on the problems in the background.

Create a 'Hunch Hour': Once a week, block out an hour to revisit old ideas or projects that didn't immediately take off. This dedicated time encourages you to look at these concepts with fresh eyes and possibly combine them with new insights.

Cultivate a Diverse Network: Engage with people from different fields and backgrounds. Exposing yourself to a variety of perspectives can spark connections between seemingly unrelated ideas, helping your slow hunches develop more comprehensively.

Embrace Patience: Remind yourself that not all ideas will come to fruition quickly. Celebrate small progressions and remain open to the possibility that some concepts may need more time to mature than others.

- Example

A scientist keeps detailed notes on her experiments, even those that fail or produce inconclusive results. Years later, she revisits her old notebooks and realizes a pattern that leads to a major breakthrough in her research.

- Example

A novelist struggles with the plot of his new book, feeling something is missing. He decides to put the project aside and starts working on another story. Months later, during a casual conversation with a friend about history, he has an epiphany that solves his plot issue, thanks to the slow hunch that matured over time.

Utilize Serendipity to Spark Unexpected Innovations

Serendipity plays a crucial role in the discovery of new ideas and innovations.

By creating conditions where chance encounters with new information or perspectives are more likely, individuals and organizations can increase the likelihood of stumbling upon unexpected innovations.

This involves being open to new experiences, diversifying sources of information, and encouraging random exploration.

Cultivating an environment that welcomes serendipity can lead to discoveries that might never have been made through deliberate search alone.

Learn DeeperExpand Your Social Circle: Make an effort to meet and interact with people from different backgrounds, industries, and interests. Attend networking events, join new clubs or groups, and be open to conversations with strangers. The diverse perspectives you encounter can spark new ideas.

Change Your Routine: Alter your daily or weekly routines to expose yourself to new environments and experiences. This could be as simple as taking a different route to work, trying out a new hobby, or visiting unfamiliar places during your free time.

Curate a Diverse Information Diet: Actively seek out information from a variety of sources. Subscribe to magazines, podcasts, and blogs that cover a wide range of topics, not just those in your immediate field of interest. This broadens your knowledge base and increases the chances of serendipitous discoveries.

Encourage Random Exploration: Dedicate some time each week to explore topics, ideas, or projects without a specific goal in mind. Use the internet, libraries, or community resources to randomly dive into subjects you know little about.

Create 'Collision Spaces' in Work Environments: If you're in a position to influence your work environment, design spaces that encourage random encounters and conversations among colleagues from different departments. Open-plan offices, communal lunch areas, and cross-departmental meetings can foster these serendipitous interactions.

- Example

A software developer regularly attends art exhibitions and music concerts, which inspire him to incorporate unique design elements and soundtracks into his coding projects, leading to innovative app features.

- Example

A marketing professional starts a book club within her company that reads and discusses books from various genres, not just business-related. This initiative leads to unexpected cross-pollination of ideas, improving campaign creativity and problem-solving approaches.

Leverage Exaptation for Creative Problem-Solving

Exaptation refers to the process of repurposing an idea or tool for a use it was not originally intended for.

This tactic encourages looking beyond conventional uses of an object or concept to find new applications that address different problems.

By fostering a mindset that is open to reimagining the purpose of existing tools or ideas, individuals and organizations can find innovative solutions to challenges.

Exaptation underscores the importance of flexibility and creativity in problem-solving.

Learn DeeperObserve Everyday Objects with Fresh Eyes: Start by looking at the tools and resources you use daily. Ask yourself if there's a different problem they could solve. This practice will help you develop a habit of seeing potential beyond the intended use.

Cross-Pollinate Ideas Across Different Fields: Make it a point to learn about areas outside your expertise. The knowledge gained can inspire innovative uses of ideas or tools in your primary field. For example, a concept from biology might solve an engineering problem.

Encourage Open-Ended Brainstorming Sessions: Whether alone or with a team, set aside time for brainstorming sessions where no idea is too outlandish. This environment fosters creative thinking and can lead to discovering new applications for old ideas.

Document and Reflect on Past Projects: Keep a journal of your projects, noting what worked and what didn’t. Sometimes, the solution to a current problem lies in an unexpected aspect of a past project. Reflection can spark ideas for exaptation.

- Example

The development of Velcro is a classic example of exaptation. Swiss engineer George de Mestral was inspired by how burrs stuck to his dog’s fur and his own clothing. He then developed Velcro, repurposing the natural mechanism of burrs for a fastening system.

- Example

Penicillin, the world’s first antibiotic, was discovered by Alexander Fleming through an unintended mold growth in a petri dish. This accidental discovery led to the repurposing of mold substances to fight bacterial infections, revolutionizing medicine.

Deeper knowledge. Personal growth. Unlocked.

Unlock this book's key ideas and 15M+ more. Learn with quick, impactful summaries.

Read Full SummarySign up and read for free!

Where Good Ideas Come From Summary: Common Questions

"The trick to having good ideas is not to sit around in glorious isolation and try to think big thoughts. The trick is to get more parts on the table." This quote from "Where Good Ideas Come From" encapsulates the essence of the book, which explores the patterns and environments that foster the birth of innovative ideas.

Steven Johnson takes readers on a journey through history, science, and technology to show how interconnectedness, serendipity, and collaboration often lead to groundbreaking discoveries. The concept of the "adjacent possible" and the importance of building on existing ideas rather than waiting for a stroke of genius were particularly thought-provoking.

Overall, "Where Good Ideas Come From" was a fascinating and insightful read that sheds light on the often unpredictable nature of innovation. If you enjoy books like Malcolm Gladwell's "The Tipping Point" or Charles Duhigg's "The Power of Habit," this book is a must-read for understanding the origins of brilliant ideas.

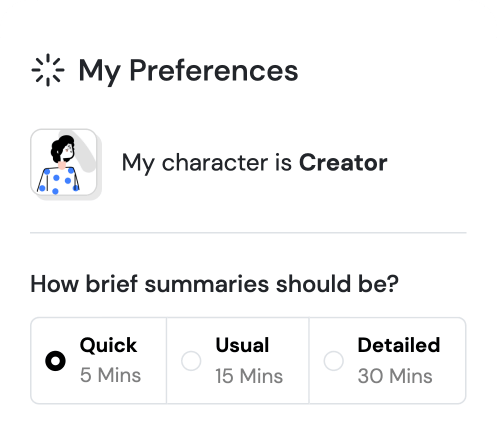

Experience Personalized Book Summaries, Today!

Discover a new way to gain knowledge, and save time.

Sign up for our 7-day trial now.

No Credit Card Needed

Similar Books

Demystifying Climate Models

Andrew Gettelman

Mathematics for Machine Learning

Marc Peter Deisenroth

Clinical Microbiology

Parslow

Medical Laboratory Science Review

Robert R Harr

Superagency

Reid Hoffman

Artificial Intelligence

Nicola Acocella

Frankenstein

Mary Shelley

The Circle

Dave Eggers

Roitt's Essential Immunology

Peter J. Delves

Laws of UX

Jon YablonskiTrending Summaries

Peak

Anders Ericsson

Never Split the Difference

Chris Voss

Smart Brevity

Jim VandeHei

The Psychology of Money

Morgan Housel

The First 90 Days

Michael D. Watkins

Atomic Habits

James Clear

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Daniel Kahneman

The Body Keeps the Score

Bessel van der Kolk M.D.

The Power of Regret

Daniel H. Pink

The Compound Effect

Darren HardyNew Books

Forex Trading QuickStart Guide

Troy Noonan

Comprehensive Casebook of Cognitive Therapy

Frank M. Dattilio

The White Night of St. Petersburg

Michel (Prince of Greece)

Demystifying Climate Models

Andrew Gettelman

The Hobbit

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Decision Book

Mikael Krogerus

The Decision Book: 50 Models for Strategic Thinking

Mikael Krogerus

Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Do No Harm

Henry Marsh