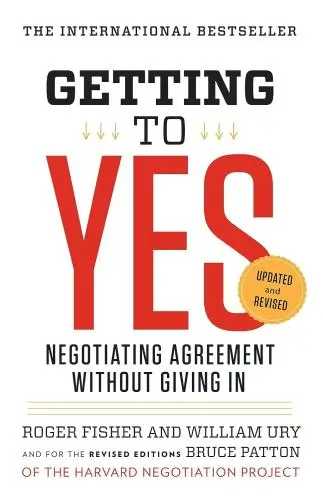

Getting to Yes

Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In

What's it about?

Getting to Yes revolutionizes the way we approach negotiations. It emphasizes the importance of collaboration and problem-solving to reach mutually beneficial agreements. Fisher introduces the concept of principled negotiation, where parties focus on interests rather than positions. This approach helps to create win-win solutions that satisfy all parties involved.

About the Author

Roger Fisher was an American academic, author, and expert in conflict resolution. Co-author of "Getting to Yes," he pioneered the principled negotiation method, emphasizing mutual interests and objective criteria. His work, characterized by practical frameworks for effective communication, significantly influenced international diplomacy and business negotiation strategies.

10 Key Ideas of Getting to Yes

Separate the People from the Problem for Clearer Negotiation

Focus on the issue at hand rather than personal attributes or past conflicts.

This approach encourages mutual respect and understanding, allowing both parties to address the problem objectively without emotional interference.

By treating each other as partners rather than adversaries, you create a collaborative environment conducive to finding a mutually beneficial solution.

Learn DeeperPause Before Responding: When you find yourself in a heated discussion or negotiation, take a moment to breathe and remind yourself to focus on the issue, not the person. This pause can help you approach the situation more objectively.

Reframe Your Statements: Instead of saying 'You always make things difficult,' try reframing it to 'I feel the process could be smoother. Can we explore some alternatives together?' This shifts the focus from blaming to problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions: Encourage dialogue by asking questions that require more than a yes or no answer. For example, 'What are your thoughts on this approach?' This invites the other person to share their perspective and contributes to a more collaborative environment.

Acknowledge Emotions Without Letting Them Lead: Recognize when emotions are high, either in yourself or the other person, and acknowledge them without letting them dictate the conversation. For instance, 'I understand this is frustrating. Let's see how we can address this issue together.'

- Example

In a workplace setting, two team members are at odds over how to approach a project deadline. Instead of focusing on past missed deadlines or personal work styles, they sit down to outline the specific challenges they're facing with the project and brainstorm solutions that accommodate both of their concerns.

- Example

During a family disagreement about holiday plans, instead of bringing up past grievances or criticizing each other's preferences, the family focuses on what the main goal is—spending quality time together. They discuss various options, considering each person's input, to find a compromise that suits everyone.

Focus on Interests, Not Positions to Uncover Real Needs

Dig deeper beyond the stated positions to understand the underlying interests.

This means asking 'why' someone wants what they're asking for and considering their needs, desires, fears, and concerns.

Understanding these interests helps in crafting solutions that satisfy the core needs of both parties, leading to more sustainable and agreeable outcomes.

Learn DeeperAsk Open-Ended Questions: When negotiating or resolving a conflict, instead of directly opposing the other party's position, ask questions that start with 'why' or 'how'. This encourages them to explain their underlying interests and opens up the conversation for deeper understanding.

Reflect and Acknowledge: After the other party shares their interests, reflect back what you've heard to ensure you've understood correctly. This not only validates their feelings but also builds trust. Say something like, 'So, if I understand correctly, you're looking for... because...?'

Identify Common Ground: Once both parties have shared their interests, identify areas of common ground or mutual benefits. This could be shared goals or values that can serve as a foundation for a solution.

Brainstorm Together: With a clear understanding of each other's interests, brainstorm solutions together. Encourage creativity and openness, focusing on how both parties' needs can be met rather than on winning or losing.

- Example

In a workplace scenario, an employee wants to work from home while the manager insists on office presence. Digging deeper, it's revealed the employee seeks flexibility due to family commitments, and the manager is concerned about team cohesion. A compromise could involve designated in-office days for team activities and remote work for individual tasks.

- Example

During a family disagreement about vacation destinations, one party wants a beach holiday, while another prefers a cultural city tour. Exploring interests reveals a desire for relaxation from one side and a need for new experiences from the other. A solution could involve selecting a coastal city with rich cultural attractions, satisfying both interests.

Invent Options for Mutual Gain by Thinking Outside the Box

Encourage creative thinking and brainstorming sessions without judgment to generate a wide range of possibilities.

This process involves looking for shared interests, exploring options that are of high benefit to one party but low cost to the other, and making the pie bigger before dividing it.

The goal is to find innovative solutions that offer mutual gains, rather than settling for compromises that might leave both parties unsatisfied.

Learn DeeperSchedule Regular Brainstorming Sessions: Set aside time for regular brainstorming sessions with your team or negotiation partners. Make these sessions a judgment-free zone where all ideas, no matter how unconventional, are welcomed. This encourages everyone to think more creatively and openly.

Focus on Interests, Not Positions: Start discussions by identifying each party's underlying interests rather than their initial positions. This shift in focus can reveal common ground and opportunities for mutual gain that were not apparent at first.

Use the 'Yes, And...' Technique: When someone proposes an idea, respond with 'Yes, and...' instead of 'Yes, but...'. This small change in language fosters a more collaborative atmosphere and builds on existing ideas to find innovative solutions.

Develop a List of Needs and Wants for Both Sides: Before negotiating, clearly outline what you need (non-negotiables) and what you want (negotiables). Ask the other party to do the same. This clarity can help identify areas of flexibility and potential for mutual gain.

Consider Third-Party Perspectives: Sometimes, bringing in an outsider's view can help break deadlocks and inspire new solutions. A third party can offer a fresh perspective on the mutual benefits that both parties might have overlooked.

- Example

In a business partnership negotiation, instead of arguing over profit splits, the parties explore creating a new joint service that leverages both companies' strengths. This could increase the total profits, making the division of profits a less contentious issue.

- Example

During a family meeting to decide on a vacation destination, instead of each member pushing for their preferred location, the family lists activities that everyone enjoys. They then look for destinations that can offer all or most of these activities, ensuring a trip that everyone can look forward to.

Insist on Using Objective Criteria for Fairness

Base the negotiation on objective standards such as market value, expert opinions, or legal precedent rather than subjective notions of what's fair.

This approach minimizes bias and ensures that any agreement reached is defensible against an external standard.

It also helps prevent the negotiation from becoming a battle of wills, focusing instead on rational problem-solving.

Learn DeeperResearch and Gather Data: Before entering any negotiation, spend time gathering relevant data. This could include market prices for similar items or services, legal documents that might influence the negotiation, or written expert opinions. Having this information at your fingertips will allow you to make strong, objective arguments.

Develop Clear Standards Beforehand: Work out what objective criteria are most relevant to your negotiation. This might mean deciding that market value is the fairest way to determine a price, or that a legal precedent should guide the resolution of a dispute. Knowing these standards in advance helps keep the negotiation focused.

Communicate Your Basis for Fairness: When you make an offer or counteroffer, clearly explain the objective criteria you're using to justify it. This not only makes your position stronger but also encourages the other party to respond in kind, leading to a more rational and productive negotiation.

Be Open to Objective Counterarguments: If the other party presents objective criteria that challenge your position, be prepared to consider their validity. This doesn't mean you have to concede immediately, but acknowledging and addressing their points shows good faith and can lead to a more equitable solution.

- Example

Imagine you're negotiating the sale of your car. Instead of simply asking for the price you want, you research the current market value of similar models in similar conditions, and use this data to justify your asking price.

- Example

You're in a dispute with a neighbor over a property line. Instead of arguing based on personal belief or desire, you both agree to hire an independent surveyor to determine the boundary based on legal land records. This objective criterion helps resolve the dispute fairly.

Know Your BATNA (Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement) for Leverage

Understand your best alternatives if the negotiation fails.

Knowing your BATNA gives you leverage and clarity about how far you're willing to go in the negotiation.

It serves as a benchmark against which any proposed agreement should be evaluated, ensuring that you do not accept terms that are worse than your no-deal option.

Learn DeeperIdentify Your BATNA Before Negotiations Begin: Spend time reflecting on what options you have if the negotiation doesn't go your way. This could be another job offer if you're negotiating a salary, another buyer if you're selling something, or another vendor if you're making a purchase.

Evaluate and Improve Your BATNA: Once you've identified your best alternative, look for ways to make it stronger. For instance, if you're job hunting, apply to more positions to potentially get more offers. The stronger your BATNA, the more leverage you have.

Keep Your BATNA to Yourself: While knowing your BATNA gives you confidence, revealing it during negotiations can weaken your position. Instead, use the knowledge to guide your decisions and know when to walk away.

Use Your BATNA to Set Your Walk-Away Point: Determine the minimum outcome you're willing to accept in the negotiation, based on your BATNA. This helps prevent you from accepting a deal that's worse than your no-deal option.

- Example

During a job negotiation, imagine your current job offers you a certain level of satisfaction and benefits. You receive a new job offer, but the terms are not as good as your current position. Knowing your BATNA (staying in your current job) allows you to negotiate confidently, asking for better terms or deciding to reject the offer if it doesn't meet your minimum expectations.

- Example

If you're selling a car and you've already received an offer from a dealership at a certain price, that's your BATNA when a private buyer shows interest. If the buyer's offer is lower than the dealership's, you know you can walk away from the negotiation, using the dealership's offer as leverage to either get a better price from the buyer or sell to the dealership instead.

Deeper knowledge. Personal growth. Unlocked.

Unlock this book's key ideas and 15M+ more. Learn with quick, impactful summaries.

Read Full SummarySign up and read for free!

Getting to Yes Summary: Common Questions

Experience Personalized Book Summaries, Today!

Discover a new way to gain knowledge, and save time.

Sign up for our 7-day trial now.

No Credit Card Needed

Similar Books

People Skills

Neil Thompson

People Skills at Work

Evan Berman

Just Listen

Mark Goulston

The Culture Map

Erin Meyer

Difficult Conversations

Douglas Stone

Give and Take

Adam Grant

Crucial Conversations

Kerry Patterson

Influence

Robert B. Cialdini

How to Win Friends & Influence People

Dale Carnegie

Never Split the Difference

Chris VossTrending Summaries

Peak

Anders Ericsson

Never Split the Difference

Chris Voss

Smart Brevity

Jim VandeHei

The Psychology of Money

Morgan Housel

The First 90 Days

Michael D. Watkins

Atomic Habits

James Clear

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Daniel Kahneman

The Body Keeps the Score

Bessel van der Kolk M.D.

The Power of Regret

Daniel H. Pink

The Compound Effect

Darren HardyNew Books

Forex Trading QuickStart Guide

Troy Noonan

Comprehensive Casebook of Cognitive Therapy

Frank M. Dattilio

The White Night of St. Petersburg

Michel (Prince of Greece)

Demystifying Climate Models

Andrew Gettelman

The Hobbit

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Decision Book

Mikael Krogerus

The Decision Book: 50 Models for Strategic Thinking

Mikael Krogerus

Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Do No Harm

Henry Marsh