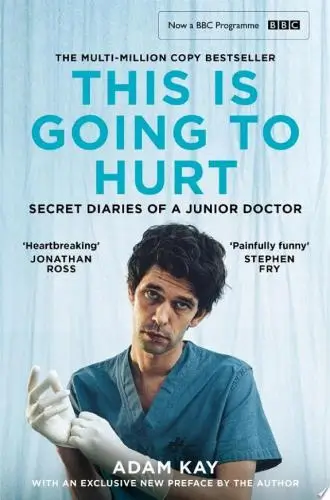

Thinking in Systems

A Primer

What's it about?

Thinking in Systems is a profound exploration of the complex webs that make up our world. From ecosystems to economies, Meadows demystifies systems theory, making it accessible and compelling. Readers learn to identify feedback loops, stocks, flows, and leverage points, gaining insights into how to effect meaningful change. Whether you're a policymaker, business leader, or curious thinker, this book equips you with the tools to see beneath the surface and understand the dynamic interconnections shaping our lives.

About the Author

Donella H. Meadows was a pioneering environmental scientist, teacher, and writer, best known for her work "The Limits to Growth." With a style that combines rigorous science with accessible prose, she explored the interconnectedness of Earth's systems, advocating for sustainable development. Her writing often delves into how small, thoughtful changes can lead to significant impacts, offering a hopeful perspective on tackling global challenges.

10 Key Ideas of Thinking in Systems

Identify and Understand the Feedback Loops in Your System

Feedback loops are fundamental components of systems, influencing their behavior over time.

Positive feedback loops amplify changes, potentially leading to exponential growth or decline, while negative feedback loops aim to stabilize the system by counteracting deviations from a set point.

Recognizing these loops allows you to predict how the system might react to changes and identify leverage points for intervention.

By understanding the nature and impact of different feedback loops, you can design strategies to enhance system stability or promote desired changes effectively.

Learn DeeperMap Out Your Personal or Work Systems: Start by identifying the key components of a system you're part of, such as your family, work team, or a project. Note how these components interact and try to identify any feedback loops. Are there processes that seem to escalate issues (positive feedback) or mechanisms that keep things stable (negative feedback)?

Monitor and Reflect on Feedback Loops: Once you've identified feedback loops, observe them over time. How do they affect the system's behavior? Is there a positive loop that's causing runaway growth or problems? Or a negative loop that's keeping things too rigid? Reflecting on these can help you understand the system's dynamics better.

Experiment with Adjustments: If you notice a feedback loop that's causing undesired effects, think about how you could intervene. Could you introduce a new process to dampen a positive feedback loop, or remove a constraint to loosen a negative one? Experiment with small changes and observe the results.

Communicate and Collaborate: Share your observations about feedback loops with others involved in the system. Collaborating on understanding and adjusting feedback loops can lead to more effective and sustainable changes.

- Example

In a project team, a positive feedback loop might be a situation where delays in one part of the project cause delays in another, leading to an escalating cycle of lateness. Identifying this loop, the team could introduce regular check-ins to catch delays early and adjust timelines accordingly, aiming to break the cycle.

- Example

In personal finance, a negative feedback loop might be a budgeting process where overspending in one month triggers automatic cutbacks in discretionary spending the next month, helping to stabilize finances over time. Recognizing and refining this loop could involve setting more precise spending limits or adjusting the cutback mechanism to be more or less aggressive, depending on financial goals.

Map Out the System to Visualize Connections and Flows

Creating a visual representation of the system helps in comprehending the complex web of relationships and interactions within it.

This involves identifying elements, connections, and flows of resources or information.

Mapping out the system enables you to see the bigger picture, revealing how components fit together and influence one another.

It's a crucial step for diagnosing issues, foreseeing potential problems, and identifying opportunities for improvement.

A well-drawn map serves as a foundation for deeper analysis and more informed decision-making.

Learn DeeperIdentify the Key Components: Start by listing out all the elements that make up your system. This could be the people, processes, resources, or information that are part of the workflow or situation you're examining.

Determine the Connections: Once you have your elements, draw lines or arrows to show how they interact with each other. Are there direct lines of communication? Does one process lead directly to another? Mapping these connections will help you see how everything fits together.

Highlight the Flows: Use different colors or symbols to represent the flow of resources, information, or energy between the components. This will help you visualize where bottlenecks might occur and where there's efficiency or inefficiency in the system.

Analyze and Adjust: With your map in hand, take a step back and look for patterns, issues, or opportunities for improvement. Ask yourself if there are ways to streamline processes, enhance communication, or redistribute resources more effectively.

Iterate and Update: Systems evolve, so your map should too. Regularly revisit and revise your map to reflect any changes in the system. This will keep your understanding current and help you stay proactive in managing the system.

- Example

Creating a visual map of a small business's supply chain to identify where delays typically occur and pinpointing potential suppliers or processes that could be streamlined for efficiency.

- Example

Mapping out the workflow of a project team to see how tasks are delegated and completed. This could reveal unnecessary steps in the process or highlight where communication breakdowns are happening, leading to targeted improvements.

Seek Out and Consider Delayed Feedback

In many systems, feedback is not instantaneous but delayed, which can significantly affect the system's behavior and stability.

Delays can cause overreaction, underreaction, or oscillations, leading to unintended consequences.

By identifying and accounting for these delays, you can better anticipate the timing and scale of system responses.

This awareness enables more accurate predictions and more effective interventions, reducing the risk of exacerbating problems through ill-timed actions.

Learn DeeperIdentify potential delays in your system: Start by mapping out the key components of your system, whether it's a project at work, a personal goal, or a community initiative. Look for areas where feedback (information that informs your next steps) might not be immediate. This could be anything from customer responses to a new product, to seeing the results of a new diet.

Adjust your expectations and plans accordingly: Once you've identified where delays might occur, adjust your timelines and expectations. If you know feedback will take time, plan for that delay. This might mean setting longer deadlines or creating interim milestones that don't rely on immediate feedback.

Monitor closely and adapt: Keep a close eye on the system, especially around the areas where you've identified potential delays. Be ready to adapt your approach based on the feedback once it arrives, even if it's later than you'd hoped. This might involve tweaking a strategy, changing a process, or even starting over with a new approach.

Communicate about delays: If you're working within a team or impacting others with your system, communicate clearly about potential delays and their implications. Setting realistic expectations can help manage frustration and ensure everyone is aligned and working towards the same goals, even when feedback is slow to arrive.

- Example

In a business launching a new product, the delayed feedback might be customer satisfaction scores or sales data. Initially, the business might not see immediate spikes in sales or direct customer feedback, leading them to question the product's viability. By understanding this delay, they can avoid prematurely altering the product or marketing strategy, giving the product adequate time to find its market fit.

- Example

For someone trying to improve their physical health through exercise and diet, the delayed feedback might be changes in body composition or fitness levels. Immediate changes are rare, and without recognizing this delay, individuals might become discouraged and abandon their health plans. By anticipating this delay, they can set realistic expectations for when they might start to see results, helping them stay motivated and committed in the meantime.

Focus on Strengthening System Resilience

Resilience refers to a system's ability to withstand shocks and stresses without collapsing into a qualitatively different state.

Enhancing resilience involves building capacity for self-organization, fostering diversity and redundancy, and maintaining flexibility.

By prioritizing resilience, you ensure that the system can absorb disturbances, adapt to change, and continue functioning.

This approach is particularly important in the face of uncertainty and rapidly changing conditions, where rigid systems are more likely to fail.

Learn DeeperIdentify and Strengthen Key Components: Take a look at your life or work systems. Identify which parts are crucial for the system's survival. Once identified, think about how you can make these components more robust or flexible to handle unexpected changes.

Encourage Diversity in Solutions and Approaches: Whether it's in your personal life, at work, or within your community, encourage and embrace different ways of solving problems. Diversity in thought and approach can act as a buffer against shocks, as it increases the chances of having a suitable solution when needed.

Build in Redundancy: Don't put all your eggs in one basket. Having backups (whether that's savings for financial security, multiple suppliers for your business, or even a plan B for your weekend outing) ensures that if one part fails, the whole system doesn't come crashing down.

Stay Flexible and Open to Change: Cultivate an attitude of learning and adaptability. When faced with new information or unexpected situations, be willing to adjust your plans or strategies. This flexibility can be a key factor in maintaining resilience.

- Example

In a business context, enhancing resilience might involve developing multiple supply chains to avoid disruption if one supplier fails. It also could mean investing in cross-training employees so that the absence of a single team member doesn't halt operations.

- Example

For personal finance, building resilience could involve creating an emergency fund, diversifying investments, and having multiple streams of income. This way, if one financial aspect underperforms, the overall financial health remains stable.

Understand and Utilize Leverage Points

Leverage points are places within a system where a small change can lead to significant impacts.

Identifying and acting on these points allows for more effective interventions.

However, leverage points are often counterintuitive; they may not be the most obvious targets for change.

Understanding the structure and dynamics of the system is key to finding these powerful spots.

By focusing efforts on leverage points, you can achieve greater results with less effort, making your actions more efficient and impactful.

Learn DeeperIdentify the System You Want to Influence: Start by clearly defining the system you're interested in, whether it's your personal life, your workplace, or a community issue. Understanding the boundaries and components of this system is the first step.

Map Out the System: Draw a diagram or write out the elements and relationships within the system. Include all stakeholders, processes, and feedback loops. This visual representation will help you see the bigger picture and potential leverage points.

Look for Patterns: Pay attention to recurring behaviors or outcomes within the system. These patterns can often lead you to underlying structures and potential leverage points.

Question Assumptions: Challenge the conventional wisdom about how things are done within the system. The most powerful leverage points are often hidden behind assumptions that go unquestioned.

Experiment Carefully: Once you've identified a potential leverage point, make small, thoughtful changes and observe the results. Be prepared to adjust your approach based on what you learn.

- Example

In a business struggling with low employee morale, instead of increasing salaries across the board (an obvious but costly solution), a manager identifies a leverage point in improving internal communication and recognition practices. By implementing regular feedback sessions and recognizing achievements, morale improves significantly with minimal financial investment.

- Example

In a community facing water scarcity, rather than immediately investing in expensive new water sources, a local environmental group identifies a leverage point in reducing water waste. They launch a campaign to fix leaking pipes and promote water-efficient appliances, achieving substantial water savings at a lower cost.

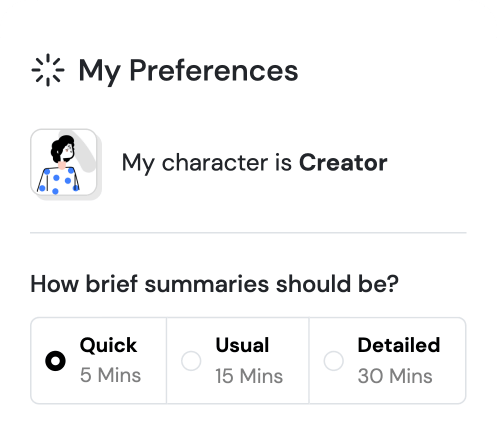

Deeper knowledge. Personal growth. Unlocked.

Unlock this book's key ideas and 15M+ more. Learn with quick, impactful summaries.

Read Full SummarySign up and read for free!

Thinking in Systems Summary: Common Questions

Experience Personalized Book Summaries, Today!

Discover a new way to gain knowledge, and save time.

Sign up for our 7-day trial now.

No Credit Card Needed

Similar Books

The Decision Book: 50 Models for Strategic Thinking

Mikael Krogerus

Emotional Intelligence at Work

Dalip Singh

Seeing the Big Picture

Kevin Cope

Leadership Is Concept Heavy

Dr. Enoch Antwi

Great by Choice

Jim Collins

The Leader′s Guide to Coaching in Schools

John Campbell

Preparing School Leaders for the 21st Century

Stephan Gerhard Huber

The E-Myth Manager

Michael E. Gerber

Leadership Is Language

L. David Marquet

Start-up Nation

Dan SenorTrending Summaries

Peak

Anders Ericsson

Never Split the Difference

Chris Voss

Smart Brevity

Jim VandeHei

The Psychology of Money

Morgan Housel

The First 90 Days

Michael D. Watkins

Atomic Habits

James Clear

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Daniel Kahneman

The Body Keeps the Score

Bessel van der Kolk M.D.

The Power of Regret

Daniel H. Pink

The Compound Effect

Darren HardyNew Books

Forex Trading QuickStart Guide

Troy Noonan

Comprehensive Casebook of Cognitive Therapy

Frank M. Dattilio

The White Night of St. Petersburg

Michel (Prince of Greece)

Demystifying Climate Models

Andrew Gettelman

The Hobbit

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Decision Book

Mikael Krogerus

The Decision Book: 50 Models for Strategic Thinking

Mikael Krogerus

Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Do No Harm

Henry Marsh